We started our farm in 2018 not knowing, the family’s history of planting arabica in the early 1900’s.

We just planted Typica seedlings sourced from the mountains above our farm. Before my daughters and I planned a coffee farm in January 2018, we were unaware that there were backyard coffee plants tucked away at the ancestral place of my husband’s family in Benguet.

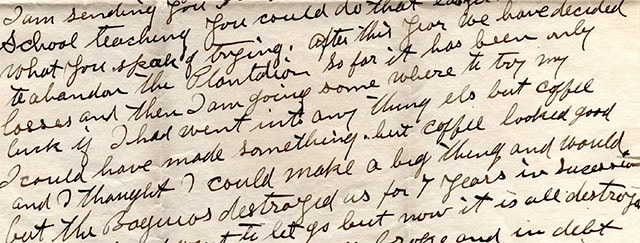

The letter

When we named our farm as “Agnep Heritage Farms”, it was in honor of my daughters’ great-great-grandmother Agnep, a Bontoc native and a backyard coffee grower who kept typica plants underneath a thick canopy of Benguet Pine, Kalasan and Alnos trees. Planting backyard coffee trees are common in Benguet. But the biggest surprise came more than a year after our first planting. Alfred Hora, the husband of Agnep, owned a coffee plantation which dates back to 1906. This was confirmed by two letters in 1913 and in 1918.

When war broke out between the Philippines and the United States in 1899, Alfred landed on the islands with American forces as a volunteer. He found his way to the Cordilleras after hostilities ended, marrying Agnep, a tribal woman and raising a daughter and four sons. Throughout all this, he kept up a correspondence with his beloved sister, Mary.

In one of his letters in 1913, Alfred tells Mary that his coffee plantation in Benguet had been wiped out by a series of typhoons, which he called ‘baguios’. Based on his letter, he mentions that the “baguios” destroyed seven years in succession thus I conclude that he planted the arabica as early as 1906.

I often wondered how the whole coffee plantation got devastated and continued on five years later. Another question is were coffee plants grown under the shade of Benguet pine (Pinus kesiya)? A letter from the postmaster to Mary on August 10, 1918 regarding the whereabouts of Alfred confirmed that he had a coffee plantation until his death in 1926. My father-in-law told me that Benguet pine was not as many as they are today. Could that be the reason behind the devastation of the Coffee Trees ? Not much protection from taller trees?

History of Benguet Coffee

Vie Reyes of Bote Central and I talked about the source of Arabica in the Philippines. Her insights inspired me to research more on its history. Wikipedia cites that Arabica coffee is believed to “have been introduced to the Cordillera highlands in the mid-19th century. According to William F. Pack, an American governor of Benguet (1909-1912) during the American colonial period, arabica coffee was first introduced to the Cordilleras in 1875 by a Spanish military governor of Benguet, Manuel Scheidnegal y Sera.”

I discovered a detailed account of the “Coffee Culture in the province of Benguet” from the 1903 Census of the Philippine Islands (page 84) that arabica was planted “in government gardens in the lowlands of the province to evaluate their potential as a regional crop. However, frequent rains and the low altitude were not ideal conditions for the plants. The next governor, Enrique Oraa, had greater success when he transplanted them at higher altitudes in 1877 and distributed seedlings among the native Igorot people. In 1881, however, the then governor, a certain Villena, attempted to coerce the natives into growing coffee by ordering them to do so. In protest, native communities destroyed arabica plantations at the advice of village elders “.

However, a native chief named Camising from Kabayan purportedly saw the benefits of the crop and introduced arabica coffee to his own people. His successes convinced neighboring communities to take up coffee cultivation on their own. Benguet coffee was part of the booming coffee industry of the Philippines during the 1880s and 1890s, which reached annual coffee exports of up to 16 million pounds.

It is interesting to note that the entire crop from the highlands of Benguet were shipped to Spain and “there disposed at fabulous prices”. None of it went to the market in Manila.

No wonder Grandfather Alfred thought planting coffee “looked good”. The aim of the government according to Governor Pack was to “foster this enterprise by every means within its power among the natives of the province, nor do I doubt that in the future the white man with his inherited enterprise will enter this territory for which nature has done so much, and make it the coffee producing province of the archipelago”.

Benguet coffee planting, then and now

Two items stand out in the 1903 report which holds true today.

1.The demand for arabica coffee will always be greater than the possible supply , according to the 1903 report

In the last decade, the demand of 6,000 – 6,500 MT local demand for Arabica is satisfied by only 3,000.00 – 3,500 MT of the local production [Matti, Philippine Coffee Board, 2010]The deficit of 50% amounts to approximately Php 690M of lost revenues.

2. The only obstacle in the way of making coffee cultivation a most profitable industry is the difficulty of obtaining suitable labor.

Our farm faced shortage of labor during the planting season. The young men are being hired abroad for construction work. Contract labor is the ideal arrangement with our lead farmer who search for family members or neighbors to help in our farm. Women find difficulty in digging when there are stones so it is the men who take over. Since planting is easier, we tap the women.

Distance in the field planting changed. The coffee plants were planted six feet apart in the early 1900s. Benguet State University recommends three to four feet apart for red bourbon. Last year, we planted three feet apart which is 1,100 plants per hectare. However, Dr. Manuel Diaz , a Coffee Food Scientist from Mexico believes 1.5 to two meters apart in our agro-forestry eco-system is more productive.

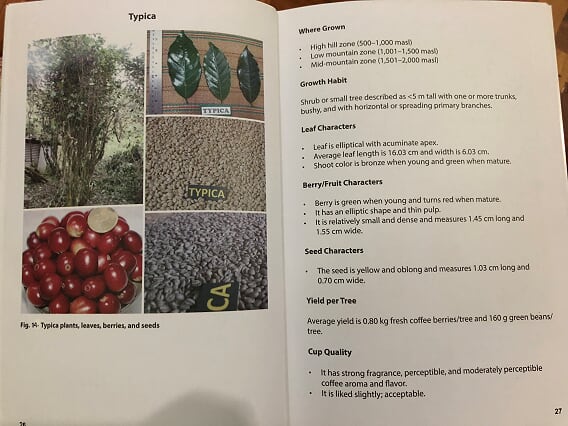

Typica, Arabica Coffee Cultivars in Benguet for Organic Production, Benguet State University , 2016

Another difference is the yield of the coffee cherries per tree. The 1903 report describes the yield of a six year old plant at three pounds or 1.4 kgs. per tree. Based on a the”Arabica Coffee Cultivars in Benguet for Organic Production” manual, the yield is 0.8 kg fresh coffee cherries per tree.

The report adds that “there is little destruction of the crop by blight” which contradicts the Wikipedia article on Benguet Coffee where it states that “coffee rust devastated the plantations in 1899 and coffee production plummeted.” Based on the letters from Grandfather Alfred, it is the “baguios” or the typhoon that devastated the coffee plantation but it did not stop him from continuing on. There is no mention of coffee rust.

Moving forward

There is plenty of room for growth. According to Euromonitor International, the Philippine coffee sector is forecast to expand by a compound annual growth rate of 11% between 2016 and 2021. The Duterte administration signed a new “Philippine Coffee Industry Roadmap 2017-2022” with the purpose of boosting the country’s annual domestic coffee output from 37,000 metric tons (MT) a year to 214,626 MT by 2022. According to the roadmap, this will bring the country’s coffee self-sufficiency level to 161% from the current 41.6%.

Despite a stable and growing international and local demand for coffee, “Philippine Arabica is not being produced, harvested and processed at a rate to meet current demands and has actually been on a sharp decline for the past several years.” Observations in the field show a shift to vegetable farming; overly shaded environment, non-rejuvenation of coffee trees and lack of post-harvest technology. Economic demand for Arabica coffee places highland farmers at a great advantage however the opportunity is somewhat negated in favor of vegetable farming, which requires higher costs and intensity of material inputs.

The obstacles for growth identified by major stakeholders in the Philippines coffee industry are: lack of government support, poor farming practices, and a lack of training for coffee farmers – in addition to the bureaucracy associated with exporting. I will write more behind the shortfall in another article.

The demand for coffee presents an opportunity for farmers and potential coffee producers. Starting a coffee farm scared me initially. I didn’t even know how a coffee tree looked like until my husband pointed it out from the backyard. We, at Agnep Heritage Farms, are eager to boost current supply but we are still learning everything from pre-production management to post harvest. Agnep farm is determined to learn from the Philippine coffee stakeholders and transfer that knowledge to existing and potential farmers. Through our farm, we want to provide sustainable benefits to farmers, processors, traders, exporters and consumers.